A PDF of the paper can be downloaded here.

How to Have Meetings That Don’t Suck | A Different Approach to Meetings

Assertion #1: Most meetings are about people sitting around a table or tiled on a zoom call trying to sound smart. They have less to do with the task at hand and more to do with career advancement. In short, most meetings...well, they suck.

Assertion #2: In meeting eutopia, meetings are about energetic debate and removing bias from the process SO THAT the group can solve for better decisions.

Assertion #3: We rarely experience meeting eutopia because of misaligned incentives. Namely, most organizations are structured in a hierarchy that makes pandering to the person(s) holding the power almost impossible to resist. At the same time, who doesn’t love sounding smart? Ego combined with incentive marks a difficult combination to overcome.

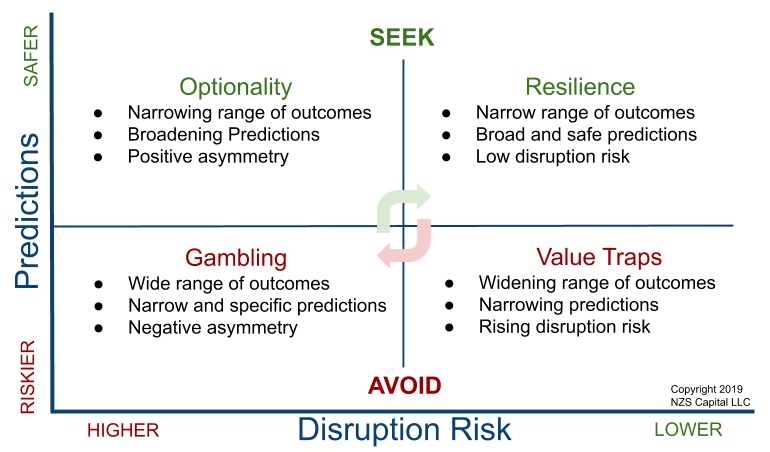

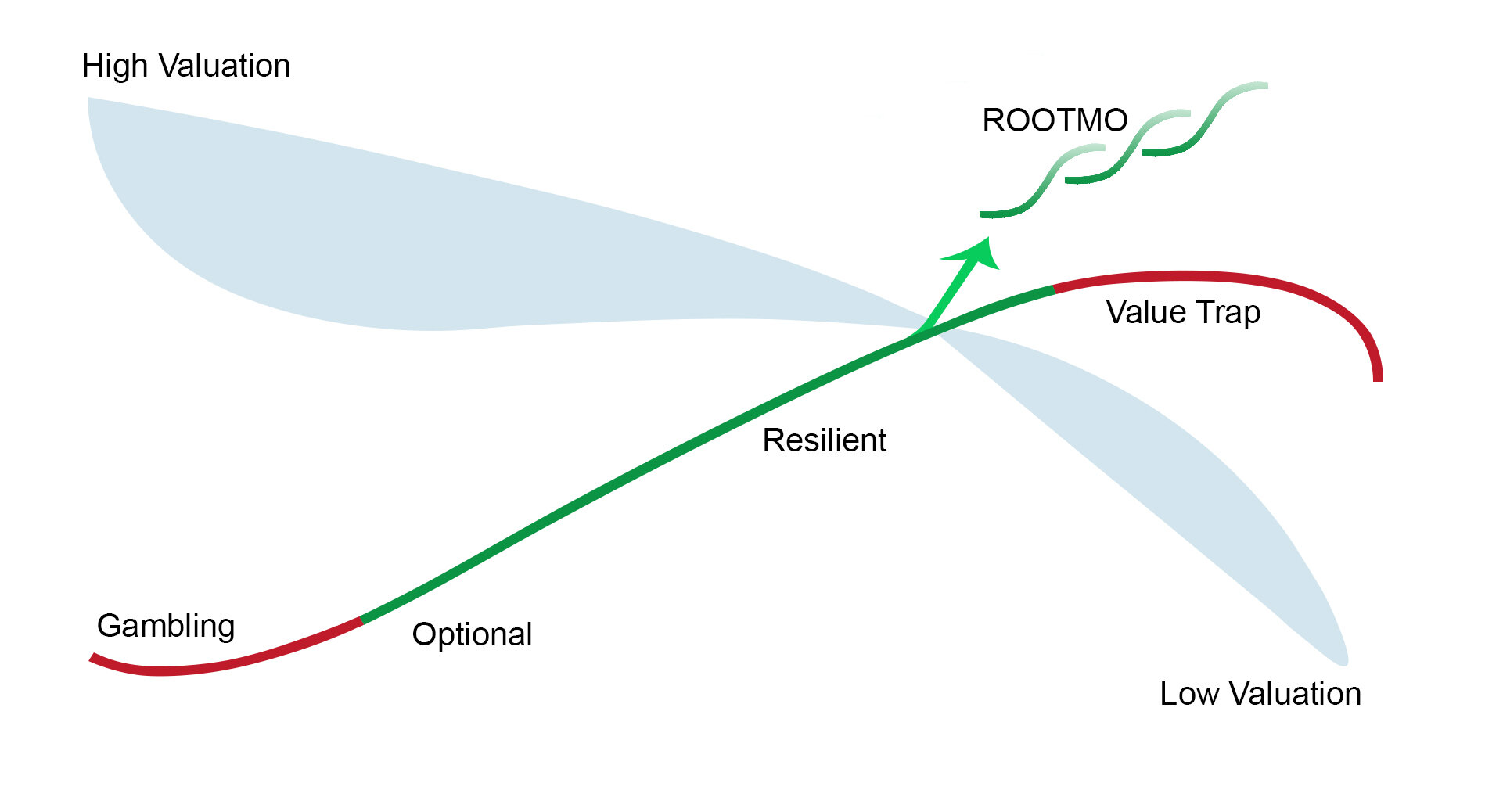

So, how do we get to a place where meetings are both fun AND result in better decision making? Here are some practical steps to improve meetings that we use at NZS Capital. While we are focused on investing and portfolio construction, these tenets should apply to any team involved in high-stakes decision making.

Seven paths to better meetings:

1. Eliminate hierarchy.

We’ve all been in meetings where we have put in days of work. As we begin to present, the senior person in the room quickly offers their opinion based on some previous bias. Heads around the table begin to nod in agreement. Our hard-fought idea quickly becomes diminished and, eventually, squashed. Is there anything more annoying than the opinion of someone who hasn’t taken the time to understand what they are talking about? For the person who has done the work, it feels demoralizing.

In the meeting room, take out the hierarchy. Acknowledge the conversational power law and take steps to flatten it.

At NZS, there is no portfolio manager/analyst dichotomy. Instead, all five investors are responsible for generating and researching ideas AND constructing the portfolio. We all have the same title: investor. And, we are all owners of the company. Our interests are aligned.

You might be thinking, “Okay, but how do you make decisions when there is no final authority?” We’ll get there...

2. Expect preparedness. Meetings should cost something – for everyone.

At NZS, we believe the power for better decision making resides in unfiltered group collaboration. To accomplish this, we don’t allow presentations. We have found that most presentations are aimed at convincing the group of something. Instead, we try to foster discussion – working together to analyze a question/topic to come as close as possible to the truth. We follow a simple structure of sending a one-pager at least 24 hours in advance. The one-pager follows a standardized format that includes several hours of homework tasks for the rest of the group, which might include listening to podcasts, listening to an analyst day, or specified reading. We also frequently do our own research beyond what’s specified in the circulated note so that we can come to the meeting ready with a unique perspective. We all learn something. Instead of the presenter teaching the group, the group members teach each other, resulting in higher quality research.

To sum up: eliminate presentations; the person doing the research should send out their work (confined to one page) 24 hours in advance and assign homework; participants should do their own independent work beyond the one-pager.

3. Avoid talking about the content of the meeting with the team beforehand.

We’ve probably all experienced politics before a meeting. It works like this: The presenter talks with teammates individually around the office, going out to coffee, whatever. They convince others of the merits of the idea beforehand and informally recruit teammates to support the idea. If the presenter is effective, they will sway the room to their point of view before the meeting even starts, rendering the actual meeting a formality with lots of head nods and little debate.

There is another less insidious form of such bias that comes from just discussing an idea that you’re excited about with a colleague during your research phase. Without intending to influence your co-worker, they too begin to see things from your point of view. It’s sort of the Heisenberg effect on pre-meeting banter. At the end of the day, decisions are a form of storytelling. We paint a picture of the future and decide which path to pursue. If we’ve already convinced people our story is true, we greatly reduce the odds of coming to a more robust decision.

At NZS, we seek to eliminate both politics and the unintended consequences of talking about a new idea by restricting talk about a topic before the meeting AND limiting the amount of time we spend together. It might sound counter intuitive to spend less time with your team. We have found, however, that time away from the team fosters diversity of thinking and more productive debate.

4. Foster an environment of trust.

In 2015, Google set out to understand what separated average performing teams from stand out performing teams. Their conclusion? It’s not how smart someone is, where they went to school, or even how good they are at their job. What separates the ordinary from the extraordinary team is psychological safety. Here’s an excerpt from a 2016 NYT article about Google’s experiment:

In other words, if you are given a choice between the serious-minded Team A or the free-flowing Team B, you should probably opt for Team B. Team A may be filled with smart people, all optimized for peak individual efficiency. But the group’s norms discourage equal speaking; there are few exchanges of the kind of personal information that lets teammates pick up on what people are feeling or leaving unsaid. There’s a good chance the members of Team A will continue to act like individuals once they come together, and there’s little to suggest that, as a group, they will become more collectively intelligent.

In contrast, on Team B, people may speak over one another, go on tangents and socialize instead of remaining focused on the agenda. The team may seem inefficient to a casual observer. But all the team members speak as much as they need to. They are sensitive to one another’s moods and share personal stories and emotions. While Team B might not contain as many individual stars, the sum will be greater than its parts.

Within psychology, researchers sometimes colloquially refer to traits like ‘‘conversational turn-taking’’ and ‘‘average social sensitivity’’ as aspects of what’s known as psychological safety — a group culture that the Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson defines as a ‘‘shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.’’ Psychological safety is ‘‘a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up,’’ Edmondson wrote in a study published in 1999. ‘‘It describes a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves.’’

When Rozovsky and her Google colleagues encountered the concept of psychological safety in academic papers, it was as if everything suddenly fell into place.

Trust is the pixie dust for better meetings. In our paper “Slowing Down Time in Organizations” we go into this aspect in more depth:

Like Pirsig’s Quality, trust can be difficult to define, but we all instinctively know what it feels like when there is trust in a team and when it’s absent. And, like Quality, trust just doesn't magically happen. Rather, trust is the product of deliberate intention, agreed-upon rules among team members, and lots of practice. Trust is also asymmetric – it can take seemingly forever to build and be lost in an instant. Trust is the “x” factor missing in average teams, yet it can catapult team productivity and success to seemingly impossible levels.

In our prior discussion of hierarchy, I said we’d come back to how decision making works when there’s disagreement among the team. Here’s how we do it:

At NZS, we don’t require consensus to put a new stock in the portfolio. We trust each other so much that even if only one person believes we should invest in a stock and everyone else disagrees, then the stock goes into the portfolio. Granted, the position size will be relatively small, but, if the thesis proves out, it can become a much bigger position over time. Surprisingly, after having implemented this practice for some time, we’ve found that the person going against the team is right most of the time. It’s also notable how infrequently this situation actually occurs (which is perhaps explained by the group being united in their goal of ferreting out the truth). And, once a decision has been made, we ALL support it, no matter our opinion. That said, we don’t stop looking for evidence that supports or disconfirms the thesis. Instead, we work harder to understand the company and help the team come to the best longer-term decision.

5. Debate the idea, not the person. Cultivate a culture of candor.

It’s all too easy for energetic debate to be taken personally. Likewise, it’s easy for debate to devolve from dissecting the idea to attacking a person. It’s important that group members develop the emotional and communication skills necessary to facilitate good meetings. We’ve learned that ideas are not tied to our identity. We’ve also found that conviction is overrated – often, it’s just another word for overconfidence. Openness to changing one’s mind when presented with superior facts remains key, which means we need to divorce our ego from the decision. We’ve come to understand that individual value to the group does not come from being right, but in helping the group ask better questions to collaboratively uncover key truths.

In his book, Creativity Inc., Ed Catmull has this to say about the unique culture of candor that permeates the meetings of Pixar’s “Braintrust”[i], a group that seeks to help struggling directors develop their ideas into amazing movies.

Candor isn’t cruel. It does not destroy. On the contrary, any successful feedback system is built on empathy, on the idea that we are all in this together, that we understand your pain because we’ve experienced it ourselves. The need to stroke one’s own ego, to get the credit we feel we deserve—we strive to check those impulses at the door. The Braintrust is fueled by the idea that every note we give is in the service of a common goal: supporting and helping each other as we try to make better movies.

Most of us have never been in meetings where debate goes beyond ego, politics, and merely trying to convince the group of an idea or agenda. It can be a vulnerable experience to change one’s mind. Too often, team members pull punches in a meeting to avoid offense. But, when the debate concerns the idea and not the person, it becomes impossible to offend (so long as individual respect governs the debate). What we have found at NZS is a sense of freedom from the need to always be right. Said another way, when you don’t feel like anyone on the team is out to get you, you can put a lot more energy into helping the group make a better decision.

Catmull shares the story of Jennifer Lee as the Braintrust worked to rewrite the storyline of Frozen:

Jenn is incredible at listening to other people. She’ll write every idea down, but if yours is an idea that seems headed for a detour or is going to take us off the rails, she’ll say, “Let’s put a pin in that.” So she doesn’t shut the room down; it’s very much the improv “yes, and” energy in the room.

Jenn recalls the offsite on Frozen: “There was no judgment. There was no doubt. It was this incredible collaboration of what inspires us. That’s the key: You have to come in generous and open, bringing all your skills with you. And you have to leave your ego at the door.”

6. Focus on calling out bias in others. Allow your own bias to be called out by others.

As we build trust, mutual respect, and a culture of candor, we can become more open to allowing others to help us see our own biases. Most of us excel at selective amnesia. We organize our memories in such a way that we are the hero of our own story. Bias is almost impossible to identify in ourselves, but it’s very easy for us to identify in others. The problem is that we seldom put ourselves in a position to voluntarily invite others to point out our own biases. It’s just too uncomfortable, for us and them! But, as we become more concerned with team collaboration than ego protection, it becomes clear that nothing is more important to the team than awareness of our individual biases.

Here are Catmull’s meeting guidelines for working towards a state of egolessness.

· Do not become attached to your ideas. (You are not your ideas.)

· Do not judge the value of your own contribution by whether your ideas are adopted.

· Put all your attention on the problem. Keep your focus on whether the idea thread is advancing or stagnating.

· Withhold quick judgement.

· As you wait to find a break in the banter in which to speak up and make your points, try not to stop listening to what is happening.

Finally, pre-mortems offer another effective way to eliminate bias in a decision by putting oneself in the future and looking back on why the decision proved to be successful or disastrous. We wrote about this process in more depth in our paper “Time Travel to Make Better Decisions”. For those wanting a deeper dive, we’d recommend the fabulous Capital Allocators podcast on conducting pre-mortem analysis with cognitive psychologist Gary Klein.

7. Embrace the initial discomfort that comes with increased debate.

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of eliminating hierarchical decision making and increasing the level of debate is that it forces the team to live with dissonance. It isn’t that dissonance is absent inside a traditional hierarchical structure, it’s just that, without an authoritarian figure, the illusion of certainty is often ripped away. It’s far more difficult to live in the reality of uncertainty and have our own overconfidence (a synonym for conviction) challenged by the group while remaining open to different points of view that are likely better than our own. The facts never fully align. We never map out our exact future path through time. There is no pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. We want certainty, we get complexity. Because trying to predict the future is largely a waste of time, adaptability becomes the goal. We find that the group often adapts far better than an individual. And adaptability is messy.

An individual decision maker will often offer the illusion of certainty due to quick decision making with conviction. However, our experience is that these decisions tend to be more bravado than substance. What really leads to better decisions is listening to and understanding others’ informed perspectives. These additional perspectives tend to increase the level of spirited debate, which, in turn, leads to new perspectives that go beyond individuals to something greater. From this foundation, the group can become more than the sum of its parts; one plus one can equal three. Instead of placing confidence in one’s opinion, we change the focus such that the confidence lies in the group – that the group will come to fantastic decisions, and those decisions will not be reliant upon anyone’s ability to predict the future better than others.

At NZS, we’ve taken the additional step of recording our meetings. We use an AI tool that transcribes the meetings so that we can become more aware of what is happening inside of our discussions. Eventually, we hope to have enough data to create a simple GPT. For example, if we made a particularly good or bad decision, we could ask the AI about the primary factors, based on what we said in the meeting, that led to that good or bad decision. As the Jesuit priest Anthony de Mello once said in his book Awareness:

What you are aware of you are in control of; what you are not aware of is in control of you. You are always a slave to what you’re not aware of. When you’re aware of it, you’re free from it. It’s there, but you’re not affected by it. You’re not controlled by it; you’re not enslaved by it. That’s the difference.

A parting thought:

Not everyone will be able to make the transition to the types of meetings we’re talking about. Unfortunately, these people are completely toxic to creating a new environment. No matter how great their individual contributions might be, they must be cut out to allow the collective intelligence of the group to thrive. There will be people that like the traditional meeting format because they get the biggest payoff from the status quo. These same folks also tend to garner the most resentment from others and tend to keep even better people from staying at the firm. Firing a toxic team member, even one with superior performance, is perhaps the single most value-maximizing thing a team can do. In our experience, editing the team to focus on a shared culture of trust and debate far exceeds the loss of any one contributor, as it allows morale to rise and collaboration to deepen. Remember, firing a team member who cannot get past their own biases and ego is great for everyone. It’s a no brainer for the team AND it’s great for the individual getting fired – there’s a whole world of toxic teams out there where they can shine.

Conclusion

Meetings don’t have to suck. As we begin to align incentives, assign homework, expect preparedness, eliminate hierarchy, and cultivate an environment of trust, meeting productivity skyrockets. There’s an aspect of holding meetings in this manner that becomes deeply uncomfortable. We must truly listen to others’ opinions and encourage them to call out our own persistent biases in the process. No matter how much we trust others, having our shortcomings highlighted never really feels great in the moment. However, that’s the price of growth.

Another drawback worth mentioning is that this manner of decision making can be painfully slow compared to command-and-control decisions. Meetings can take longer. Getting to the root of a question through debate can result in numerous dead ends before there is a breakthrough. Frustrations can run high. This can take some people by surprise, especially those who were previously in control. It’s easy to give up on the process too soon. However, at NZS, we have consistently found that, as we push through initial discomfort and resist the urge to come to snap decisions, our thought processes are richer, the insights more nuanced and defined, and our conclusions are consistently higher quality. Oh yeah, and our meetings don’t suck.

Sources:

Duhigg, Charles. “What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team.” The New York Times, Feb. 25, 2016. (https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html)

Slowing Down Time in Organizations. NZS Capital, 2021. (https://www.nzscapital.com/news/slowingtime)

Catmull, Ed. Creativity Inc. Random House, 2014; Revised Edition 2023.

Time Travel to Make Better Decisions. NZS Capital, 2021. (https://www.nzscapital.com/news/time-travel)

Seides, Ted, host. “Conducting Pre-Mortem Analysis with Gary Klein, Paul Johnson, and Paul Sonkin.” Capital Allocators, episode 109, September 22, 2019. (https://www.capitalallocators.com/podcast/conducting-pre-mortem-analysis/)

De Mello, Anthony. Awareness. Image, 2023.

[i] In recent years Pixar has seen somewhat less commercial success combined with higher than historical expenses. In an updated version of Creativity Inc. (The Expanded Edition) published in 2023, Catmull discusses what appears to be an evolution in the Braintrust culture at Pixar away from the primary creative directors and towards the collective opinion of the employees. While it’s hard to comment as outsiders, we wonder if this shift in culture may have contributed to lower commercial success.